Only Up From Here: 2024’s State of Fintech and the Hero’s Journey

We’re at the scary part of “the hero’s journey” in fintech, with a bottom for funding and a BaaS crisis, but we’re about to enter a new, exciting stage.

While the story of public market fintech over the last three years has been perplexing, a retrospective analysis reveals a few simple lessons.

While the story of public market fintech over the last three years has been perplexing, a retrospective analysis reveals a few simple lessons.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

5 Takeaways

Characteristics of Market Cap Resiliency

Model for Market Cap Resilience

Unlocking the Fintech Formula: Today’s Core Value Drivers

Building the “Perfect” Fintech Company

Where We Go From Here

Roaring back from the fears of economic collapse at the beginning of COVID, digital distribution and servicing became a must-have for financial services disruptors and incumbents alike. Consumers, awash with cash, opened more accounts, explored new ways of investing, saving, and spending money, and trusted the digital provision of financial services more than ever before. Businesses invested for growth at unprecedented levels, creating a frenzied labor market, a record pace of new product development and a high mark in company burn.

Enticed by the increased demand, the opportunity to sell into some of the largest markets in the world, and the vision of strong founders, VC funding reached record levels: according to Pitchbook, in 2021, venture investments in fintech reached $121.6b, a 153% YoY increase in global VC deal value that was more than the total value invested in 2019 and 2020 combined.1 Fintech was the darling of VC, accounting for $1 for every $5 of venture funding.2

The last 12 months have been more sobering – some have described 2022 as the morning after the party. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent shockwaves throughout the global economy, including financial services, and heightened our sense of insecurity. With inflation surging, the Fed began increasing interest rates in March, changing the fundamental economics under many companies, especially fintech companies whose performance is more directly tied to the cost of capital.3 Resulting both from (1) the high pace of capital deployment into fintech in 2021, which meant many companies were well-capitalized heading into 2022, and (2) the crash in public market valuations that challenged sky-high private market growth valuations, venture investing in fintech companies came down considerably. As of Q3 2022, according to CB Insights, global fintech funding fell 38% vs 2021 to hit $12.9B in Q3 2022 — matching Q4’20’s level.

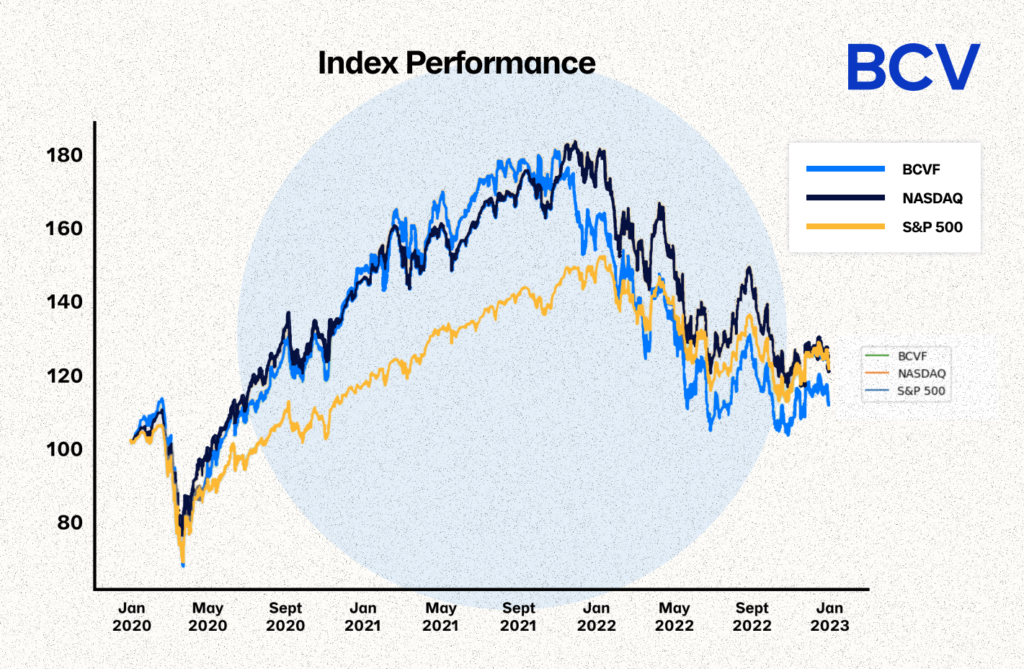

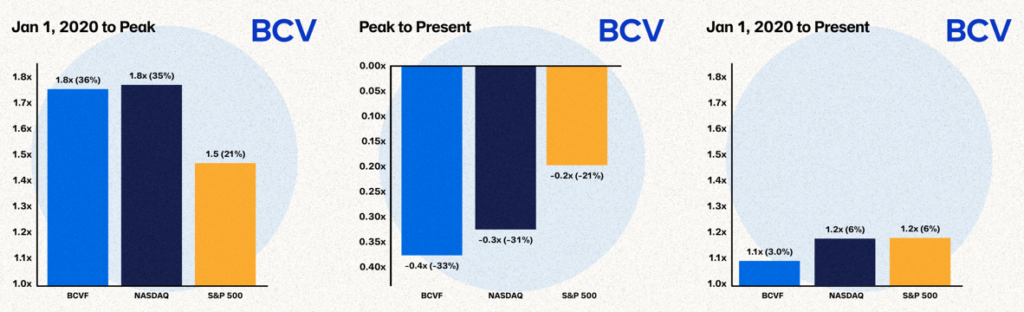

Looking at the market deceleration over the past 15 months, it is widely understood at this point to those who follow the markets that publicly-traded fintech companies fared worse than their non-fintech counterparts. We can see this below: a market cap-weighted index of 121 selected publicly-traded fintech companies (we’ll call it “BCVF”) rose by more than the S&P 500 and about the same as the NASDAQ, peaked earlier, but then dropped by more from its peak than both other indices, and ultimately ended up lower than the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ relative to Jan 1, 2020. But, why?

We share this analysis with the hope that our findings can inform and encourage the many talented founders and management teams building fintech companies. Do not let the volatility of the past three years obscure the greater arc of the fintech story: we are in the early innings of transforming our financial world, the market opportunity is massive, and our conviction in the value creation in this space has never been stronger.

Five lessons we can take away from reviewing the public market’s treatment of fintech over the past 3 years:

1. The Emperor Has No Clothes

| What Happened | How to Understand It |

|---|---|

| You weren’t crazy if you thought the markets unfairly punished next-gen fintech companies earlier this year: market valuations of next-gen fintech companies dropped by more than can be explained by any financial metrics during the first market trough around June 30, 2022. Next-gen fintech companies lost more than their valuation premium above the legacy players, which shows it wasn’t a “true up” but rather the market viewing newer entrants differently. | The illusion of relative valuation in public markets depends at least in part on self-deception on the part of those being deceived, much like in the famous story The Emperor Has No Clothes. The story the market believed as the market began to fall in 2022 was that next-gen fintech companies were over-valued because growth was over-valued, so their valuations should fall more than their legacy fintech peers. But, the next-gen fintech valuations fell by more than could be explained by growth or profitability. |

2. The Tortoise and the Hare

| What Happened | How to Understand It |

|---|---|

| By the second market trough on September 30, 2022, this next-gen fintech penalty abated, and a company’s financial performance could more or less explain the full variation in market cap contraction. The companies with the most resilient valuations were more profitable, served enterprise or mid-market business customers, were growing well but not too fast, and did not have balance sheet based business models. | The more slowly but consistently moving tortoise is more successful than the more quickly and erratically moving hare. Similarly, the market reset exposed the next-gen fintechs as hares who need to adopt the principles of the consistent legacy fintechs to achieve similar valuations. |

3. Goldilocks and the Three Bears

| What Happened | How to Understand It |

|---|---|

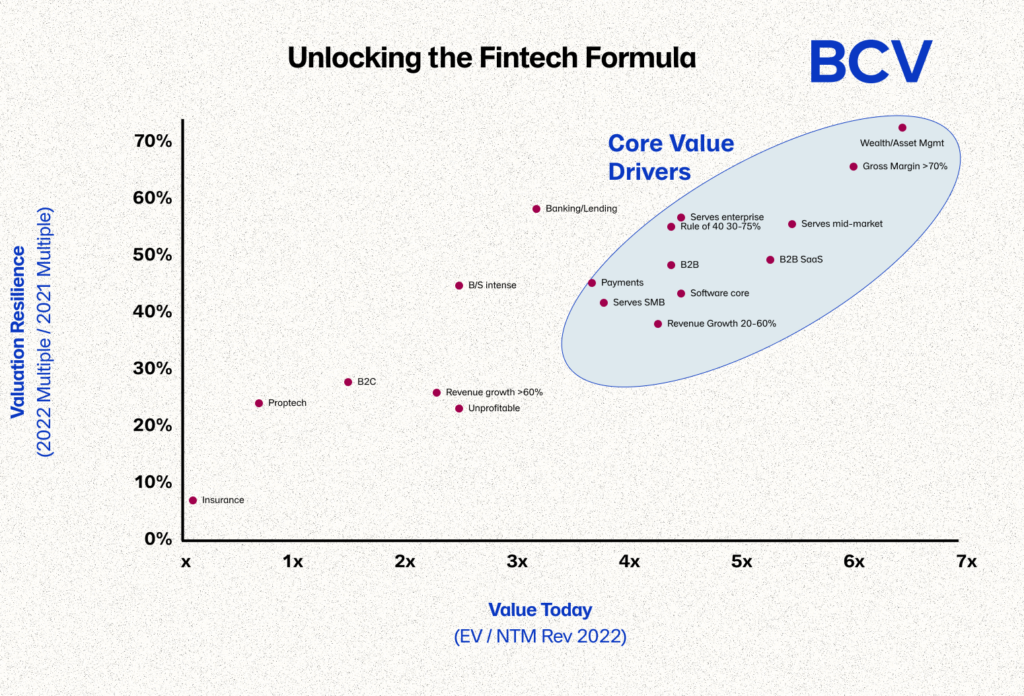

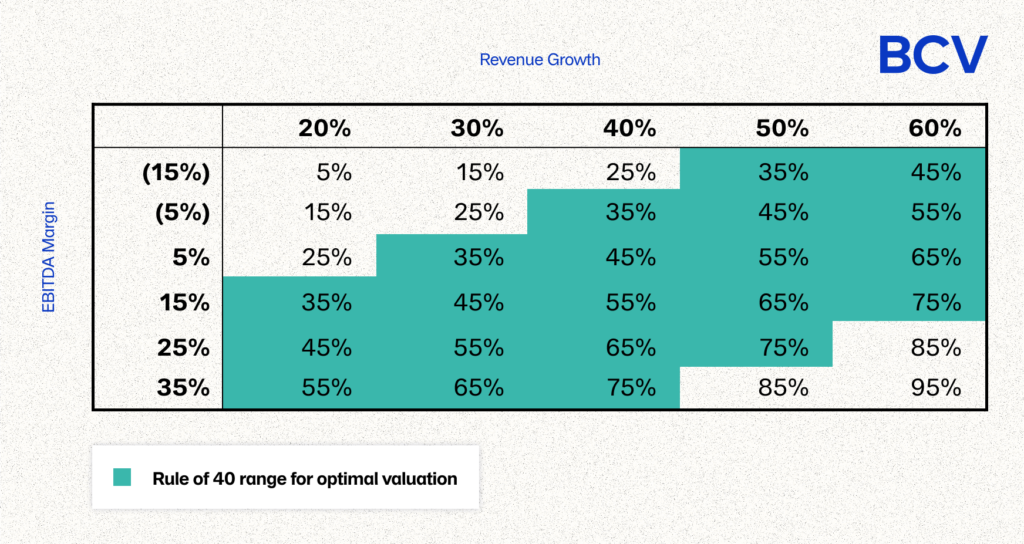

| Looking at the characteristics associated with higher market multiples, some are consistent over the past three years. The characteristics associated with higher market multiples have been remarkably resilient over time, including higher gross margin, a moderate level of revenue growth, software at the core, and serving B2B. To maximize valuation multiple today, profitable growth is more important than maximizing profitability or maximizing growth. We recognize this is harder to execute than it is to suggest. | In this old fairy tale, a little girl named Goldilocks tastes three bowls of porridge: the first is too cold, the next is too hot, but the third one is just right so she eats it all up. Similar to the lesson in this old fairy tale, the companies with the highest valuations over time are those that are not growing too quickly, or those growing too slowly, but those growing “just right.” |

4. The Three Little Pigs (an alternative)

| What Happened | How to Understand It |

|---|---|

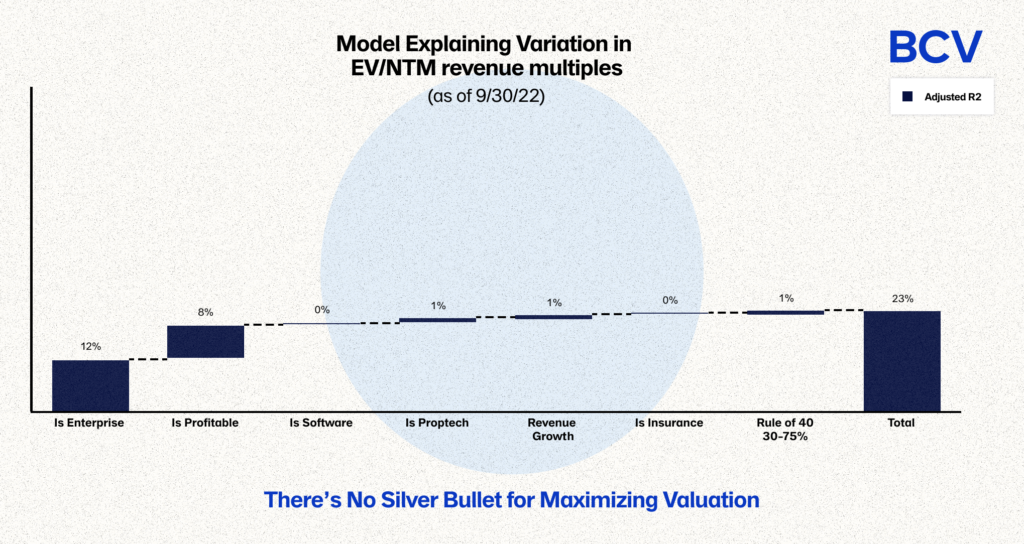

| There is no silver bullet for maximizing valuation — statistically or practically. Using all observable financial and business model characteristics for companies, the best model we can create to maximize valuation today explains less than half of the variation in valuation multiple. In other words, no single observable characteristic is insurmountable. What you can control is your strategy and how well you execute it. However, there are fewer degrees of freedom for error the more characteristics a company has that are correlated with lower valuations. | In the old fairy tale, three pigs build houses out of different materials to protect themselves from the big bad wolf. The first two pigs build houses out of straw and sticks, which are blown down by the wolf. The wolf cannot destroy the house made of bricks by the third little pig. Similarly, we can identify the durable material characteristics to build stronger companies today. That said, it is POSSIBLE to build a strong enough house out of sticks – with the right strategy and detailed approach (it’s just a lot less likely to withstand the big bad wolf). |

5. The Ugly Duckling

| What Happened | How to Understand It |

|---|---|

| Fintech is a broad category that encompasses many types of businesses, and so it follows that not all fintech companies should converge to the same multiples. Great fintech companies will be built across sectors, customer segments, and with different business attributes (like software intensity and balance sheets). While it’s a fool’s errand to build with the markets in mind, we expect valuations of private fintech companies to normalize for fundamental characteristics as valued by the public markets. | In the story of The Ugly Duckling, the would-be duck spends the early part of the story trying to fit in — only to find out that he would never fit in with the ducks anyway, and just needed to be patient to become a swan. The story teaches us that we’re not all the same, and one’s true self will come out over time. Similarly, even if it’s tempting for private markets to use similar multiples to value different types of fintech companies over time, we believe the impact of different business models on cash-generation potential at-scale will inevitably be internalized over time. |

The universe of companies include 121 public fintechs trading on US, European, and Chinese exchanges across the categories of payments, lending/banking, insurtech, wealth/asset management, B2B SaaS (with embedded payments), and proptech. We include both consumer and B2B companies. While we exclude traditional banks, insurance companies, real estate companies, and asset managers that were not started with the premise of operating technology first, we do still include legacy fintechs, even though they are considered to be less tech-forward than their next-gen counterparts. Beyond reported financials and trading metrics, we also added a number of additional variables to the dataset including employee count and growth, categorical descriptors of the companies (e.g. B2B vs B2C, legacy vs next-gen fintech). A full review of the companies can be found here.

When was the market peak? We define the “peak” as the date when the market reached its highest value. Here, we consider the day of maximum index values (based on company-level market cap). As seen in the chart above, the BCVF index peaked on October 19, 2021. For the purposes of this analysis, we’re using the closest fiscal quarter end dates for these dates, setting the peak at September 30, 2021. From this peak, the BCVF index dropped for the next several months, reaching an initial trough around June 30, 2022, and then after a short-lived rebound, reaching a second trough on September 30, 2022. The lowest point of the BCVF index to-date was October 14, 2022, a year after the peak, almost to the day.

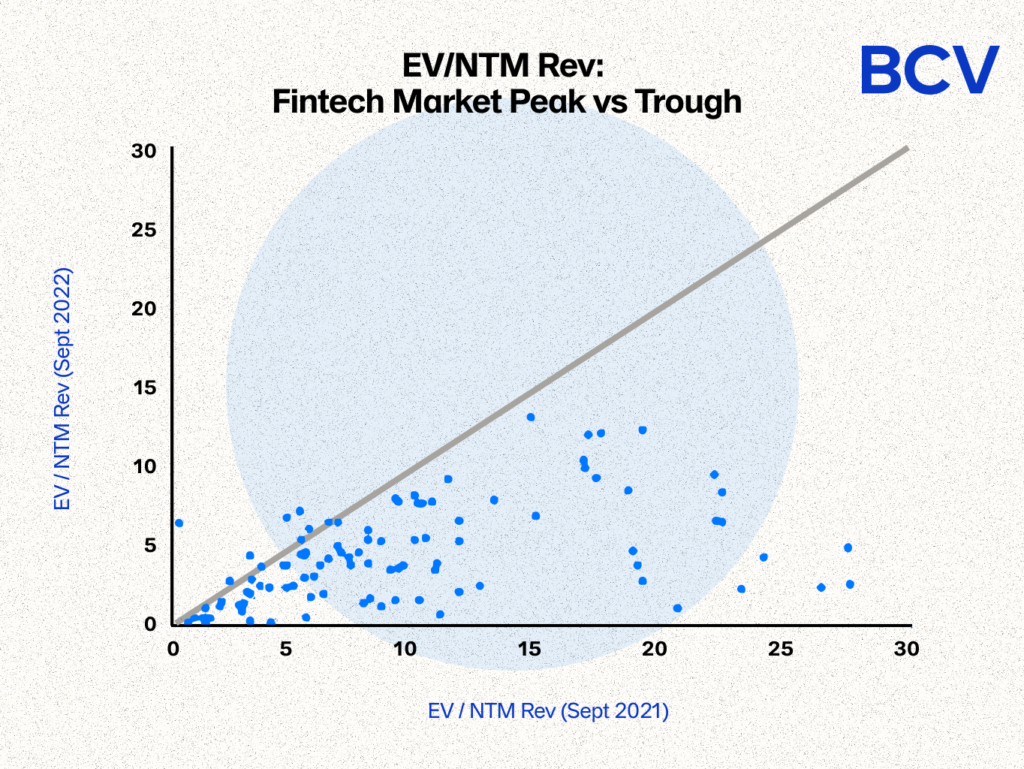

It’s an understatement to say that we saw a massive loss in value across fintech companies from peak to trough. At peak on September 30, 2021, there were 110 publicly traded fintech companies for a total market cap of $3.31T. The median EV/NTM revenue multiple was 8.0x. Over the next year from September 30, 2021, to September 30, 2022, an additional 11 fintech companies IPOed bringing the total count to 121. At initial market trough on June 30, 2022, the same 110 publicly traded fintech companies from 2021 had a market cap of $2.13T, or a 36% loss of $1.18T, and the loss was about the same on September 30, 2022. Altogether, on September 30, 2022, the group of 121 total fintech companies had a market cap of $2.08T – the 11 newly minted publicly-traded fintech companies only had a $31B in market cap. Across the full population, the median EV/NTM revenue multiple on 9/30/22 was 3.7x.

How can we make sense of this loss? We started by looking at various characteristics of companies to see what was correlated with change in market cap, and how strongly. What we saw mostly confirmed our expectations. Let’s walk through these relationships one-by-one.

Starting with financial characteristics of companies:4

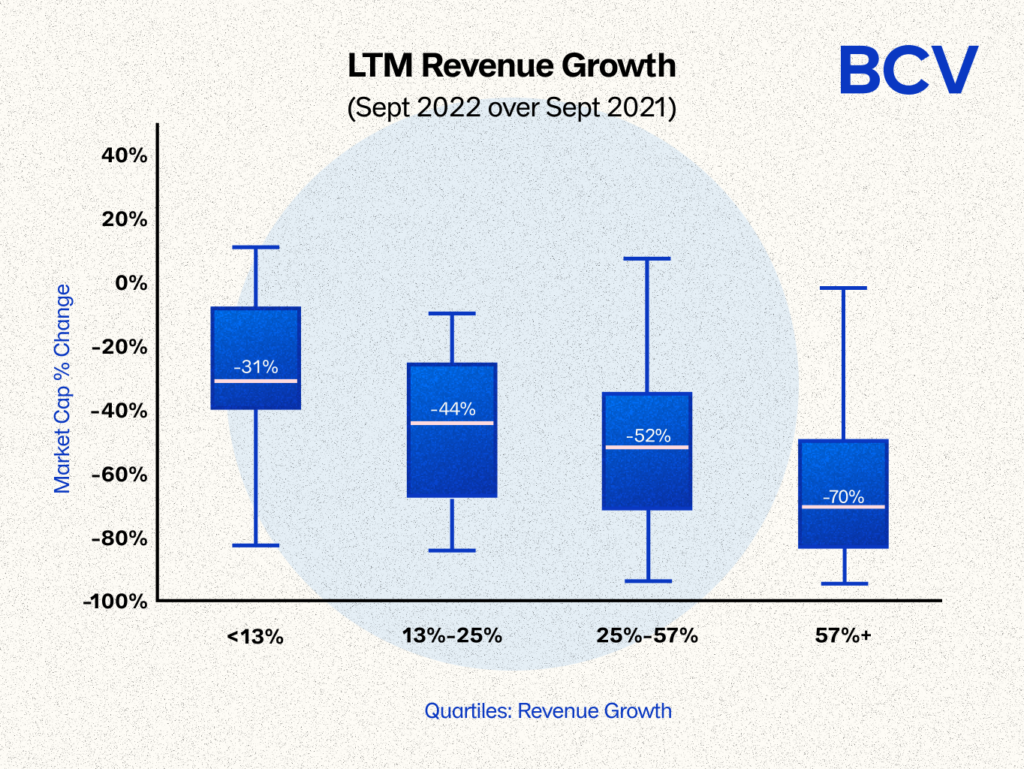

The faster a company was growing → the larger the drop in market cap.

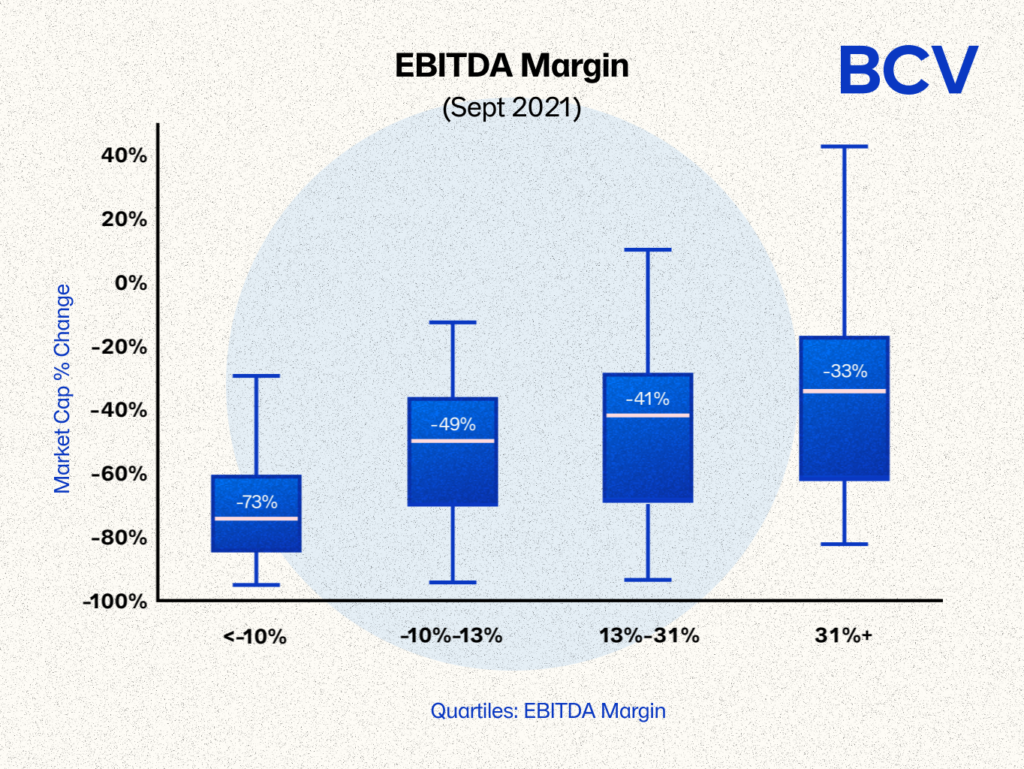

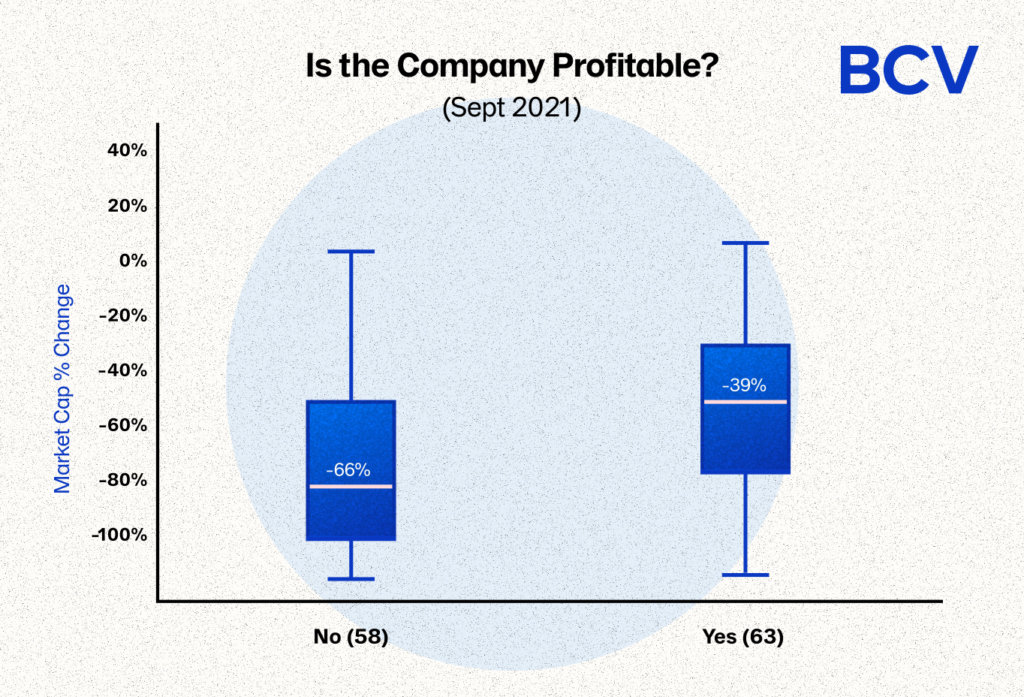

The higher the EBITDA margin → More resilient value. More profitable companies retained more value than those that were burning.

The EBITDA margin relationship is even clearer if we separate profitable and unprofitable companies.

These two effects combine to create a barbell relationship with Rule of 40: Companies in the band with a Rule of 40 around 40% were more resilient whereas those very low (<25%) and very high (>70%) saw a larger drop in market cap.

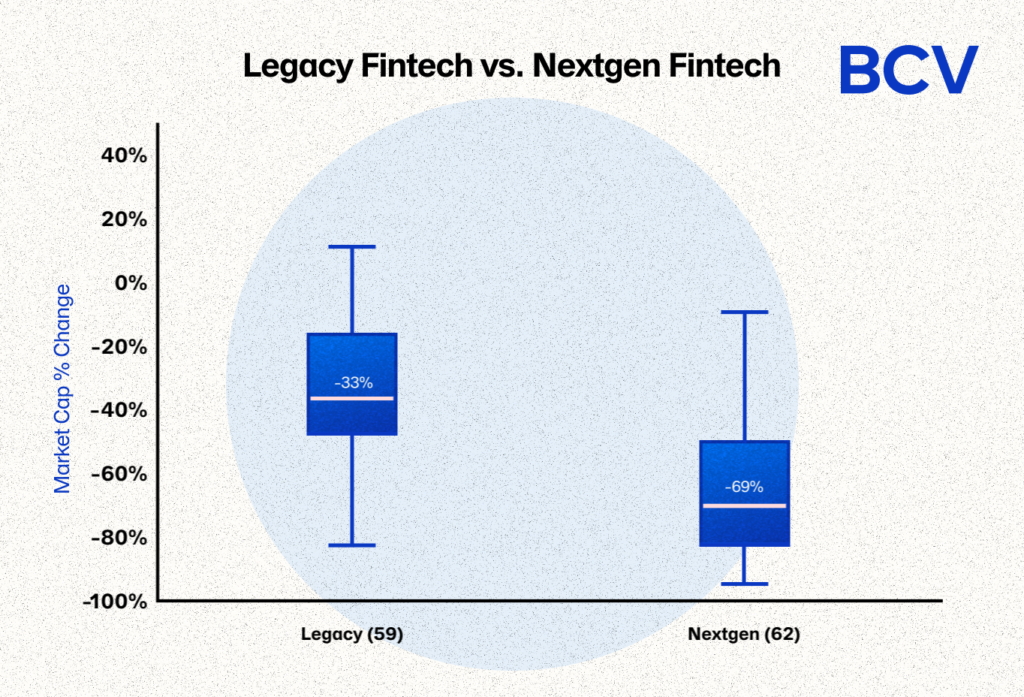

If legacy fintech company → Less drop in value. Next-gen fintech companies were more likely to be faster growing and less profitable.

Turning to some business model characteristics:

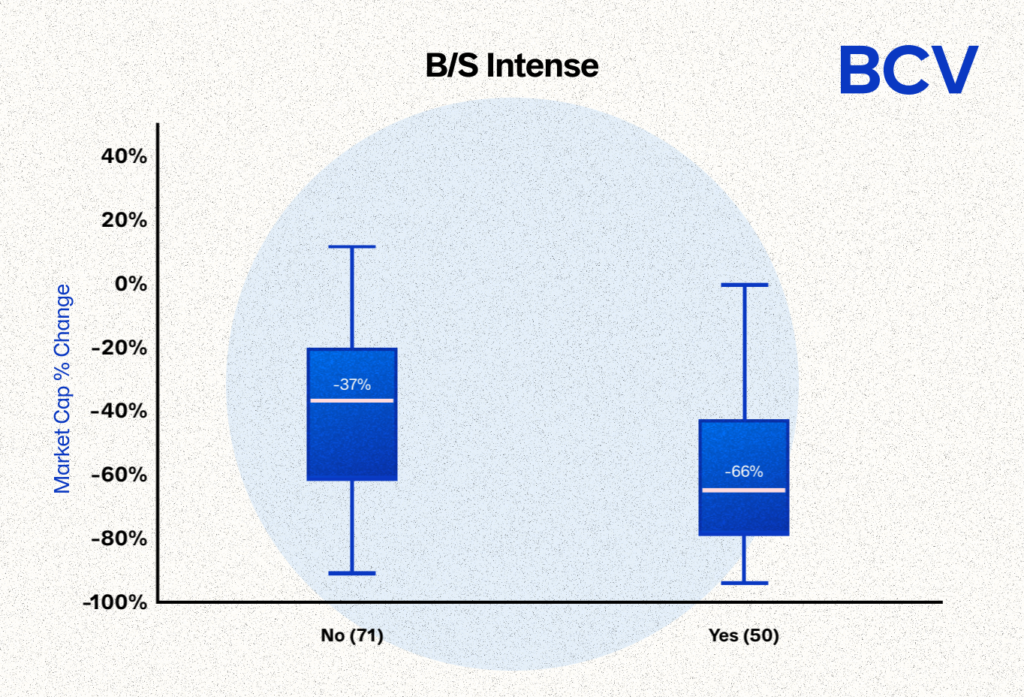

If no balance sheet → Less drop in value.

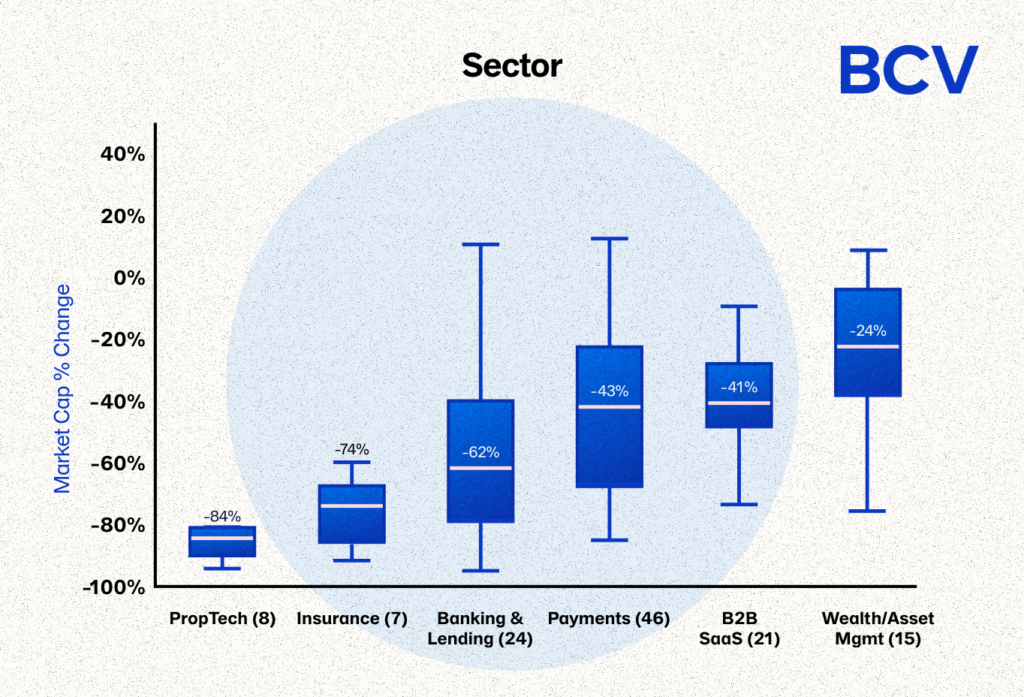

There was a wide dispersion in performance across categories. Insurtech and proptech fared the worst whereas B2B SaaS and wealth / asset management performed best. There was a wide dispersion in outcomes within banking & lending and payments, owing both to the count of companies in both categories as well as the diversity of business models.

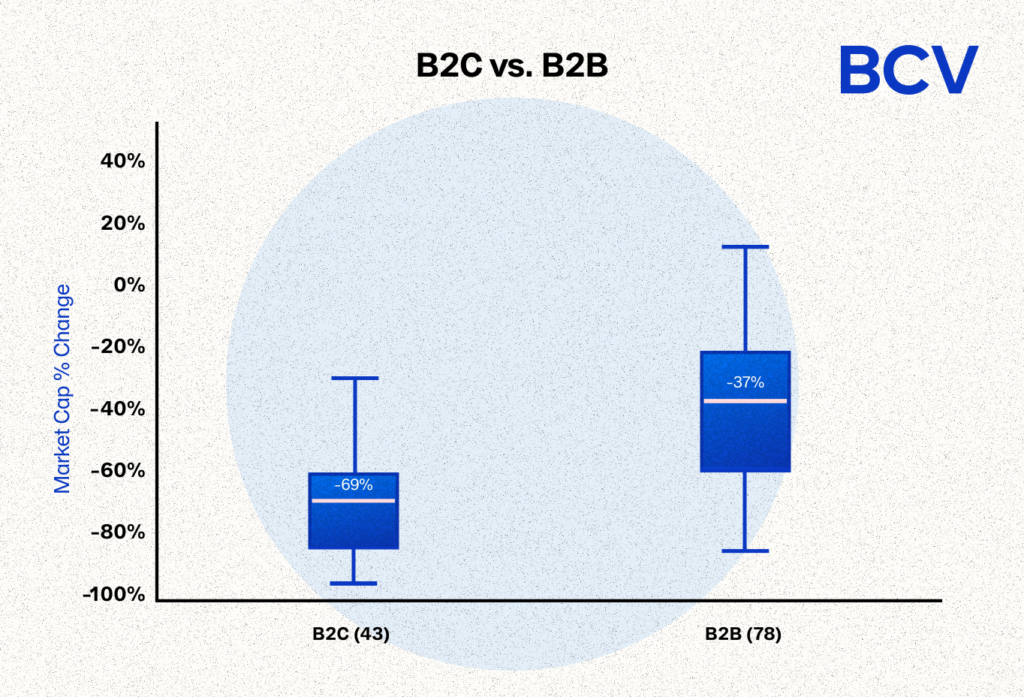

Across markets: B2B companies saw less of a drop in value than B2C.

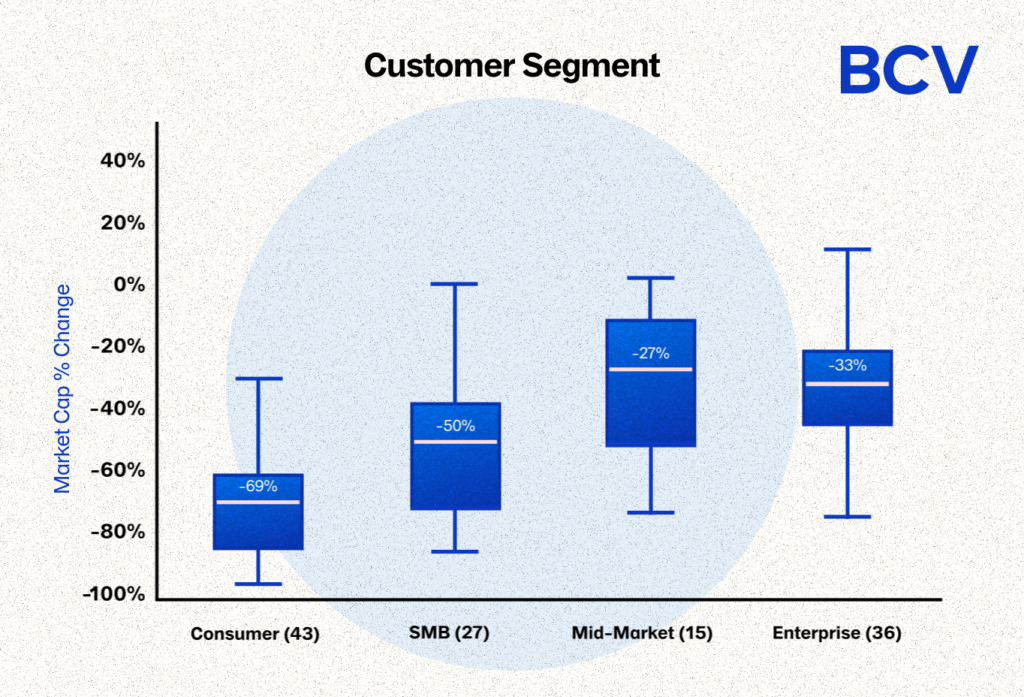

Even within B2B, we saw dispersion where those companies serving smaller customers – consumer and SMB – saw a larger drop in values than those serving larger customers – mid-market and enterprise.

When reviewing the list of characteristics correlated with change in market cap, we can reason through how many of them are related to one another. For example, wealth/asset management and payments companies are much less likely to have balance sheets whereas insurtech, proptech, and banking/lending companies are much more likely to have them. Similarly, nextgen fintech companies are more likely to have lower EBITDA margins, be smaller, and be growing faster. It’s helpful that the findings are internally consistent, but this begs the question: what are the most important characteristics to explain the variation in market cap across companies?

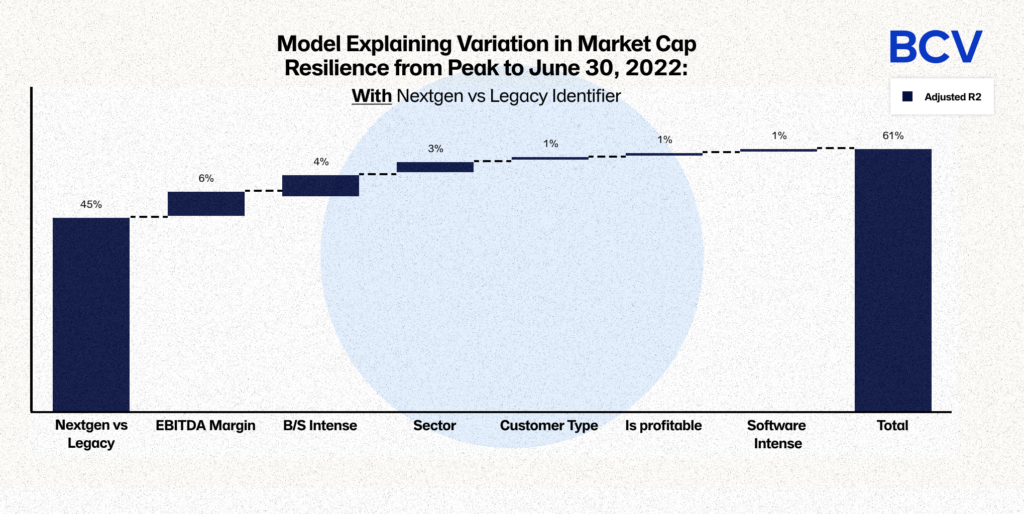

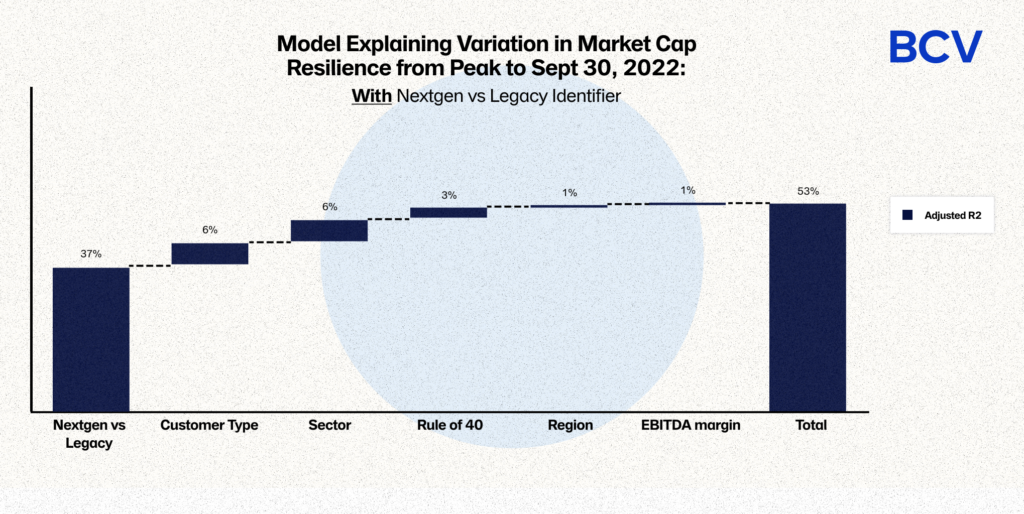

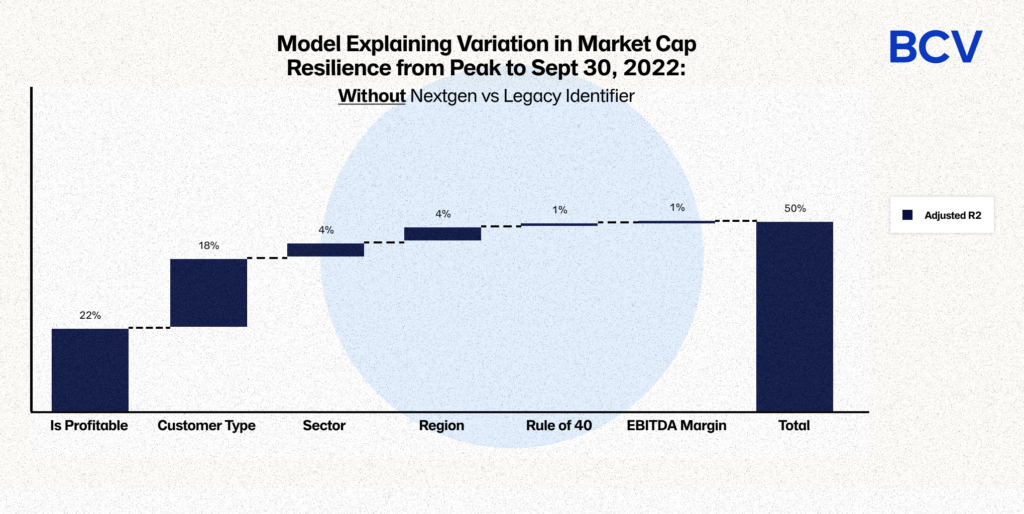

To answer this question, we ran a stepwise regression analysis with the goal of explaining as much of the resilience in market cap as possible, i.e. for the stats nerds among us: maximizing the adjusted R² of the multivariate regression. What we found was surprising. Looking at the first market trough around June 30, 2022, considering the entire set of variables, the single biggest driver is whether or not a fintech company is classified as “legacy” or “next-gen.” Legacy fintech companies retained more value from peak to trough than next-gen fintech companies, alone explaining 45% of the variation in market cap performance. We can build a model from there that explains 61% of the differences in market cap resilience.

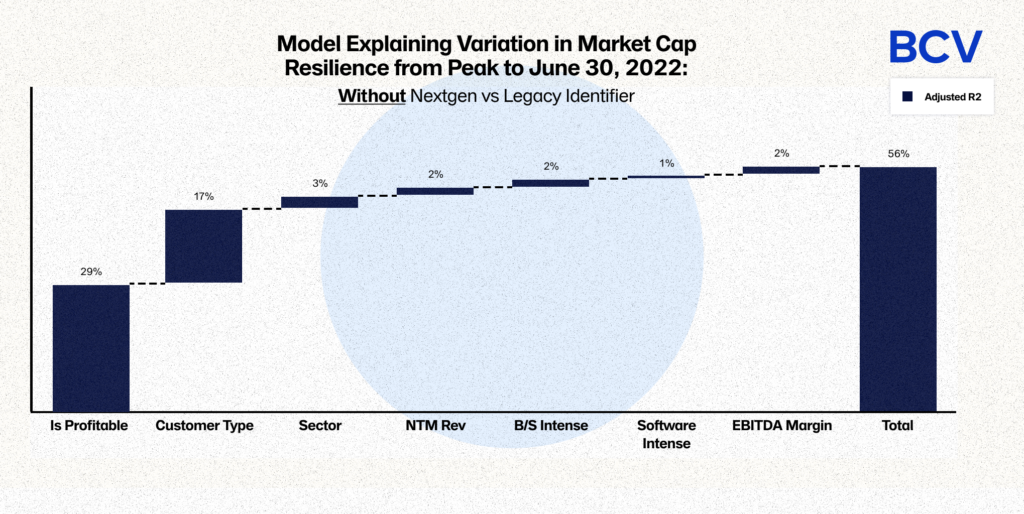

What if we try to build a model excluding the legacy fintech vs nextgen fintech variable? This model only explains 56% of the resilience in market cap performance.

This is a significant finding. In other words, as of June 30, 2022, the loss of market cap value for nex-gen fintech companies vs their legacy counterparts cannot be explained by observable financial or business model characteristics. It’s not that next-gen fintech companies are less profitable and faster growing than their legacy peers, and the public markets turned from favoring growth to favoring profitability, so therefore the next-gen fintech companies lost. Rather, there was something about the inherent qualities or market perception of nextgen fintech companies that the public markets soured on!

Did this hold during the second BCVF trough on September 30, 2022? No, the effect of the next-gen vs legacy fintech variable was significantly more diluted. To see this, we can look at the stepwise multivariate regression including the next-gen vs legacy fintech variable, which achieves a R² of 53%, vs the multivariate regression without the next-gen vs legacy fintech variable, which achieves a R² of 50%. In addition, the importance of next-gen vs. legacy shrinks from 45% to 37% when included.

You’ll also see that the best R² achieved in either model for September 30, 2022, is less than the best R² achieved in either model for June 30, 2022. In other words, the overall variation in market resilience can be less accurately modeled by the second market trough. This is good news! This shows that the idiosyncratic characteristics (eg, TAM, market leadership, quality of management, etc) of each company became more important for overall company value vs the variables we can measure, as expected.

Putting this all together:

To look backwards, we focused on % change in market cap because this enabled us to focus on resilience under two different valuation regimes. Market cap is larger for larger and more highly valued companies, and those with a greater % change can be either due to relative size or drastic change in valuation methodology.

To look forwards, we shift focus to valuation multiples, or the ratio of the company’s enterprise value (EV) to its NTM revenue. In effect, this adjusts for company size. EV also takes into account a company’s net debt, so can identify company strengths or weaknesses that market cap cannot. We choose the multiple EV/NTM revenue because it’s the most extensible across sectors (though we typically use EV/NTM GP multiples internally for fintech companies).

Let’s get grounded in the facts: looking at a simple chart of EV/NTM revenue multiples for each company from peak to trough, we see that nearly all companies saw a significant drop in multiples (i.e., companies below the diagonal “parity” line have lower multiples in Sept 2022 than they did in Sept 2021).

As we can see, there was a significant shift in median multiple from 2021 to 2022. While this is fairly well understood now, the more interesting and important findings are one layer deeper. Below, we graph company characteristics based on current EV/NTM revenue multiple (x-axis) and valuation resilience, i.e. what % of 2021 multiple is the 2022 multiple (y-axis).5

Here is the Fintech Formula, a map for building fintech companies with resilient valuations:6

Finally, can we build a “perfect” next-gen fintech company to maximize valuation multiples?

The answer is no. Similar to the process we used above to understand the characteristics correlated with market cap resilience, we can build a stepwise multivariate regression to maximize R², or the variation in EV/NTM revenue multiple today that can be maximally explained by observable characteristics. The best model we can produce, summarized in the chart below, has an adjusted R² of only 23%.

The fact that it’s not possible to combine observable company characteristics in a way that maximizes public market multiples is one of the most important findings of this analysis: there is no silver bullet for maximizing valuation. The importance of characteristics may change over time depending on the macro environment and other facts totally outside of your control. We think this is good news for all of us working in fintech as founders, operators, and investors: the particular merits of your company, most importantly your strategy and how well you execute it, matter significantly more for determining valuation multiples than any set of observable financial or business model characteristics.

In conclusion, where do we go from here?

—————————

We’re at the scary part of “the hero’s journey” in fintech, with a bottom for funding and a BaaS crisis, but we’re about to enter a new, exciting stage.

Relay is reinventing banking with more software and intelligence for every small business owner.

Generative AI can make companies more efficient, but customers have more to gain from it than they do — including in banking, commerce and medicine.