Selective State Space Models: Solving the Cost-Quality Tradeoff

As AI is increasingly used in production scenarios, costs are mounting. Are alternative architectures the solution?

Automation is modularizing point products across functions and domains, becoming the vehicle for deploying decisioning ML in the enterprise and catalyzing a new generation of process layer startups.

Over the last few years at UiPath, my dear friend & co-author Yash (check out his upcoming newsletter here!) led acquisitions of companies like ProcessGold and CloudElements, and go-to-market deals with behemoths like E&Y and JP Morgan, pushing the limits of process orchestration and driving automation in some of the world’s largest companies. Business leaders consistently expressed their dissatisfaction with packaged suites like SAP and Salesforce, driving their investments in UiPath to better run and automate their business processes.

My customers at Atlassian echoed this sentiment. Jira, although synonymous with developer workflows, is a customizable workflow engine used to track legal processes, asset management, talent workflows, and more. As a result, we focused heavily on introducing automation, trying to become the orchestrator and executor. Bain Capital Ventures has been a long-time believer in the process layer, and we are privileged to have companies like Alloy Automation, Moveworks, and Atlassian in our portfolio.

A new class of orchestration software is emerging, downgrading the role specialized suites have historically played. We’ve dubbed this area software defined process orchestration, and it’s changing both how we think about value creation and the role of machine learning in the enterprise.

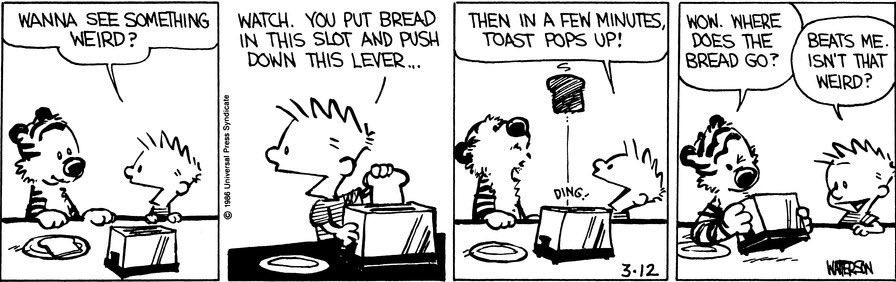

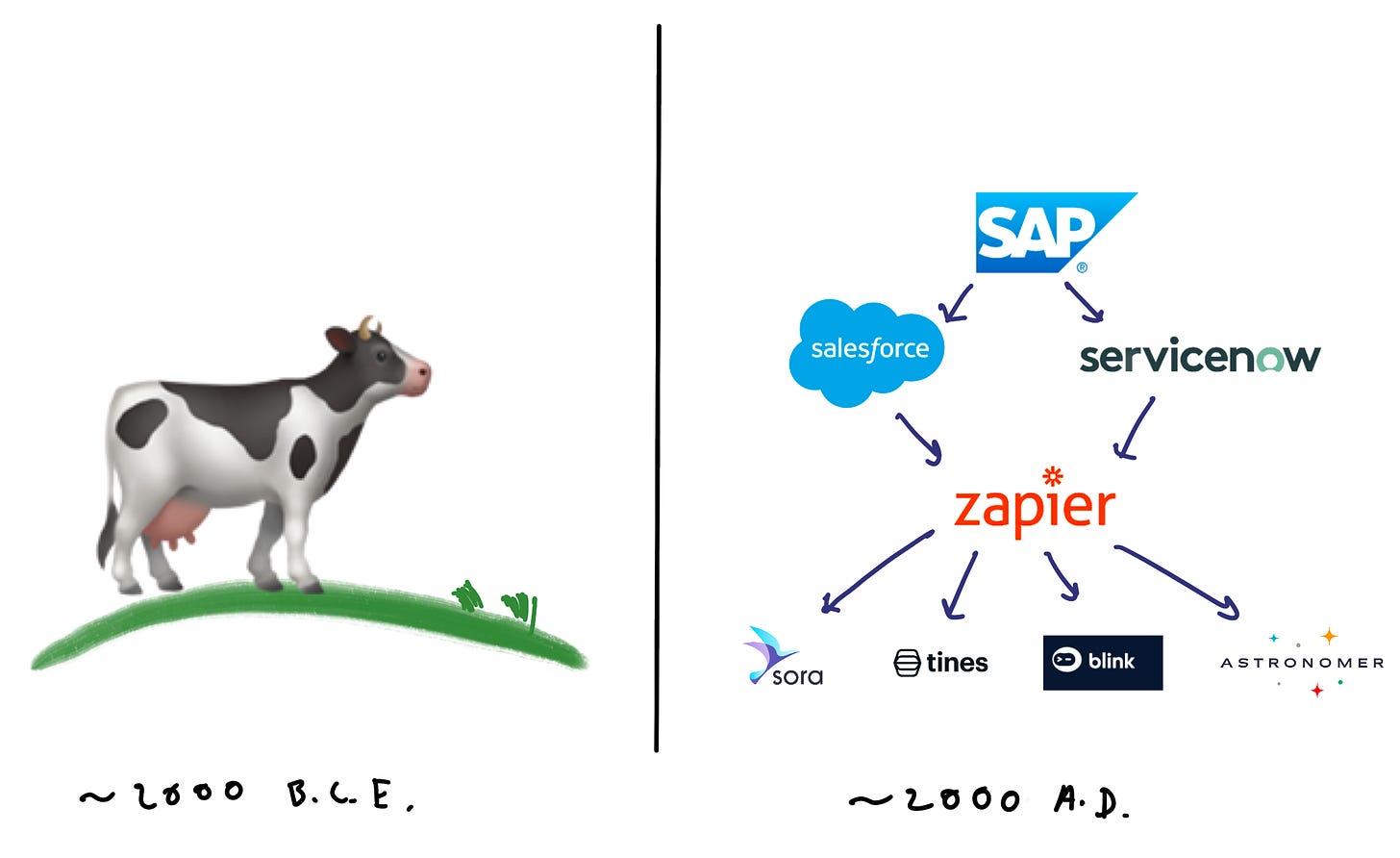

Humanity has always strived to automate; when we started farming, we “automated” food finding by using livestock to orchestrate the food workflow (grazing, producing fertilizer, providing meats, etc.). Post-industrial revolution, we automated manufacturing with robots, and post-digitization, we’re automating business processes with software (ServiceNow, MoveWorks, UiPath).

Starting with Manufacturing Resource Planning (MRP) software in the ’70s and Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) software in the ‘80s, vendors like SAP (f. 1972), JD Edwards (f. 1977), and BAAN (f. 1978) provided front-to-back visibility into not just business, but also the processes that kept business chugging along. ERP was excellent for connecting product to profit. Suddenly, you didn’t need to run through procedures in the back office every time your company recorded a transaction. Companies wanted the same productivity gains in other parts of their business, demanding custom ERP implementations.

Vendors partnered with firms like Deloitte and Slalom to create certifications for educating an army of implementation consultants. Long implementation cycles were necessary to customize the software enough to reflect the specific processes that were being digitized. Eventually, core ERP diffused into specialized suites, like CRM for customer acquisition, HCM for people, ITSM for IT processes, etc.

Specialized suites could elasticize more processes, but increasingly best-of-breed software necessitated data movement between various apps, leading to API proliferation.

This has done wonders for base-level connectivity; APIs are the nervous system of the Internet, but they leave gaps to be filled in by humans or custom connectors, creating more manual work. Engineering time is the most precious resource companies have, leading to gigantic pro-services spend ($1.1T annually) or custom tooling investments ($500b annually).

Every company has some hardware underpinnings, either owned or leased, some layer of platform services running on top, and an application layer that leverages the platform to do meaningful things. Humans (or automations we create) move data from one app to another, defining the process layer: the secret sauce that differentiates one company from another.

Humans bring tribal knowledge & adjudication, while automations bring business rules and logic. For example, Goldman Sach’s processes helped it avoid the Archegos trading loss, and Brex’s processes allowed it to steal a march on small business cards from Citi. To avoid customization + consultant hell, enterprises are increasingly investing in tooling at the process layer.

The stack that powers common business processes like P2P (procure to pay) and O2C (order to cash)

ServiceNow decoupled the process layer from business apps. By baking ITSM business logic into a workflow engine, ServiceNow customers could automate their service desk and capture both business and IT policies. Strategically, the workflow engine was customizable enough to reflect new processes, while focusing on ITSM addressed the cold-start problem. ServiceNow has extended the playbook to other areas like Customer Service Management, HR Service Desk, etc.

ServiceNow and its peers are capitalizing on the monolithic POV of their predecessors; SAP expected to automate processes running across SAP’s ERP, CRM, and SCM offerings. Reality is different: front-to-back SAP shops are rare. Companies are instead combining best of breed apps with custom tools to solve their needs. Noticing the trend, vendors are investing in the process layer (Salesforce acq. MuleSoft, SAP acq. Contextor, Microsoft acq. Softomotive) to avoid being modularized and abstracted away.

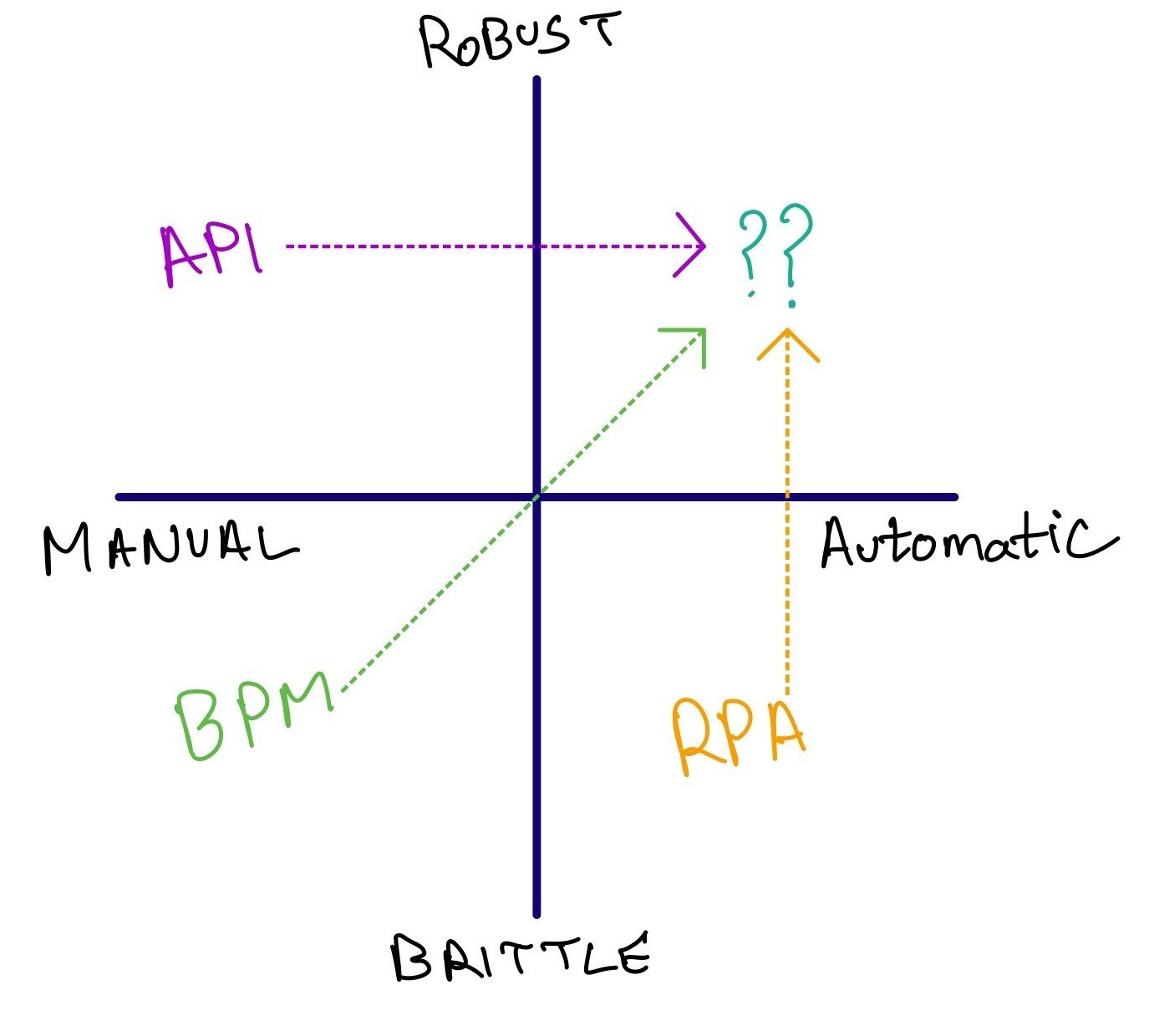

Processes are implemented through APIs, BPM, and RPA, and stitched together via humans. Each element of this stack presents tradeoffs:

Humans orchestrate the work being done via each of these. For example, if you’re a customer success rep at a SaaS company, you might commonly apply an X% discount to Y set of customers to prevent churn. You might have APIs connecting various datasets together to show you customers & spend, BPM workflows helping you document the change in billing for each customer, and RPA to execute incentive creation in your CRM.

The market lacks an automated, robust set of tools with minimal human intervention.

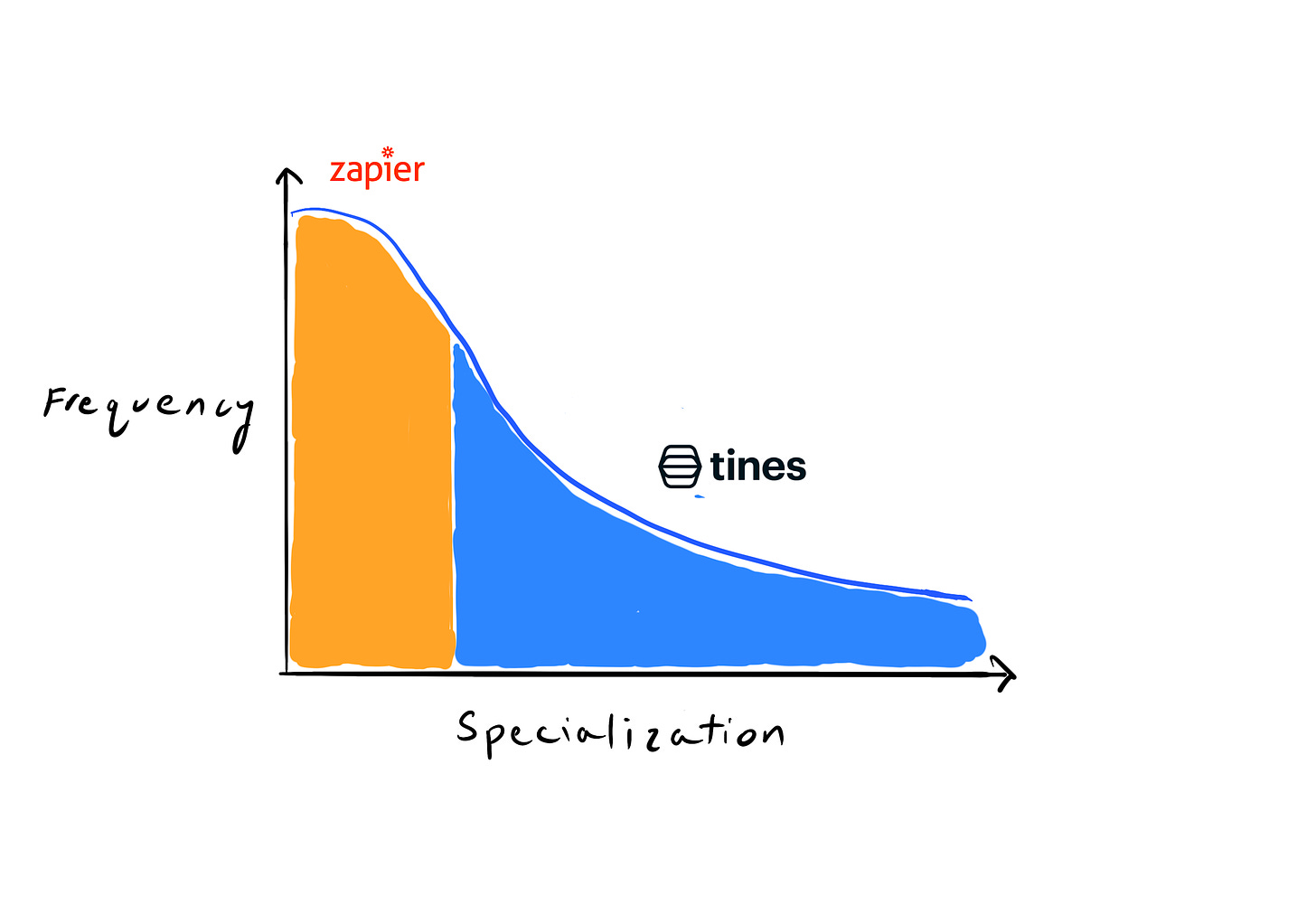

Horizontal orchestrators like Zapier are brilliant for automating the head, but lack coverage for the long tail of specialized processes. A security engineer might use Zapier to push users from SurveyMonkey to Okta, but can’t use Zapier for any meaningful security workflows, creating a market opportunity for companies like Tines.

Zapier and its horizontal peers aren’t incentivized to go deep, but several specialized functions (like security) are slowed by a mountain of manual work and human intervention. Market sizes in each vertical are expanding as companies seek the benefits of automation in more processes (like recruiters focusing on sourcing more candidates, rather than mucking around in ATS screens).

Startups targeting specific processes and verticals with automation will define the next generation of process automation.

Beyond administrative ease, SDPO brings ancillary benefits in data structuring. When processes are executed manually, emitted data is lost. At best, we can scrape screens (missing state) or ingest logs (missing intent). SDPO startups can collect execution data as they run, emitting not just a greater volume of data, but also usable, computable data.

All of this data can be fed through decisioning models to optimize processes. Peak and Sisu are working on the decisioning side of this workflow. Revisiting the customer success example:

If you’re a customer success rep at a SaaS company, you might commonly apply an X% discount to Y set of customers to prevent churn.

Using the data generated by process orchestrators, we can get to a point where X and Y are automatically computed, freeing up the collective brain space of product managers, rev ops analysts, success leaders, and more.

There are four secular shifts:

Processes are the lifeblood of any company hitting meaningful scale. We’ve made strides in capturing processes with RPA, integrating disparate tooling with APIs, and tracking processes with BPM. Each of these innovations are laying foundation for the future of software automation: process orchestration applied to specific functions, turning every company into an automation company.

We are in the first innings of SDPO with a lot more innovation yet to come

As AI is increasingly used in production scenarios, costs are mounting. Are alternative architectures the solution?

Cube is the standard for providing semantic consistency to LLMs, and we are investing in a new $25M financing after leading the seed round in 2020.

In this edition of “In the Lab,” Amit Aggarwal explains why he’s building an AI startup in BCV Labs after selling his company The Yes to Pinterest.